Charlie Chaplin

What can be said about Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin in a few lines? Criticised while alive for old fashioned direction and over-sentimentality, and critically eclipsed after his death by Buster Keaton, he was nevertheless the first global superstar. His films remain - quite simply - very, very funny; whether it's the Little Tramp in the Yukon, Adenoid Hynkel toying with his globe, or Monsieur Verdoux trying to murder another wife.

Charlie Chaplin was the first great star of a new and exciting entertainment industry – the cinema. Less than 3 years after leaving Fred Karno’s English music hall troupe and signing up to make motion pictures for Mack Sennett in California, Chaplin was making a film a month, earning an incredible amount of money, and thanks to the universal appeal of silent films was instantly recognisable across the world.

He was the first global superstar. Famous everywhere, imitated by many, loved by millions, featured in comic books, toys and other early forms of merchandising, and with a glamorous lifestyle and plenty of sex and (later) political scandals.

For the first thirty years of his film career, all of his films were enormously successful, both critically and commercially. The iconic comedic moments are almost too numerous to remember, but as examples, think of him boiling and eating his boot in “The Gold Rush”. Or attacked by monkeys on the highwire in “The Circus”. Or trapped in the literal and metaphorical cogwheels of the industrial age in “Modern Times”.

The only real criticisms of his work were aimed at his penchant for pathos and sentimentality, and his old fashioned direction.

It’s true that he sometimes aimed for tears; but usually as well as, rather than instead of, laughter. Critics point to his painful separation from “The Kid”, that look at the end of “City Lights” (hopeful or pathetic?), and Calvero dying in the wings in “Limelight”. But you mustn’t forget the comedy before and after.

And maybe his direction was often basic. But this was as much the result of a positive desire to have his performance centre stage at all times as it was the consequence of his inability (or unwillingness) to take advantage of technical advances and to move away from the largely static set-ups employed in the very early days of film-making.

But there are also many critics and film-makers who acknowledge him as a master of mise-en-scene, including Martin Scorsese, who has an enormous admiration for “Monsieur Verdoux” in particular.

Verdoux is a wonderful film. Unpopular at the time of its release in 1947, and virtually castigated in the US for its politics, it reads today as a sublime black comedy. Full of darkness and contrasting light, and deft comic touches. Perhaps Chaplin was preaching a little. He had certainly done so before, especially in his plea to mankind for tolerance and understanding at the end of “The Great Dictator”.

And he would do so again, in his bitter attack in 1957 on the country which had by then exiled him, in “A King in New York”. But even in his films with a message, it’s never much of a wait for Chaplin to switch from politics to pure unadulterated comedy.

Some of our current Charlie Chaplin stock

-

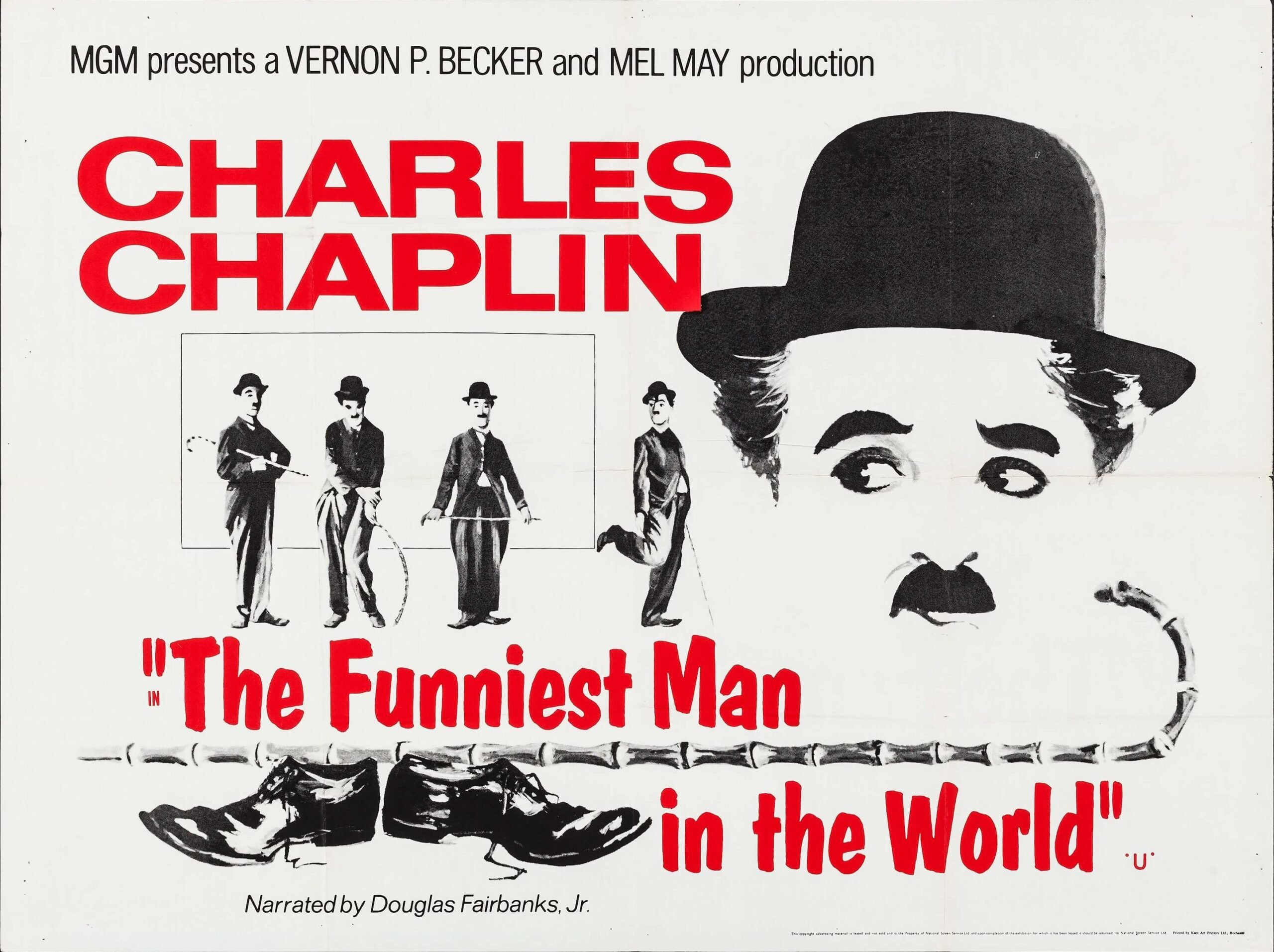

The Funniest Man in the World

£295.00In stock

Format: QuadView -

The Gold Rush

£250.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

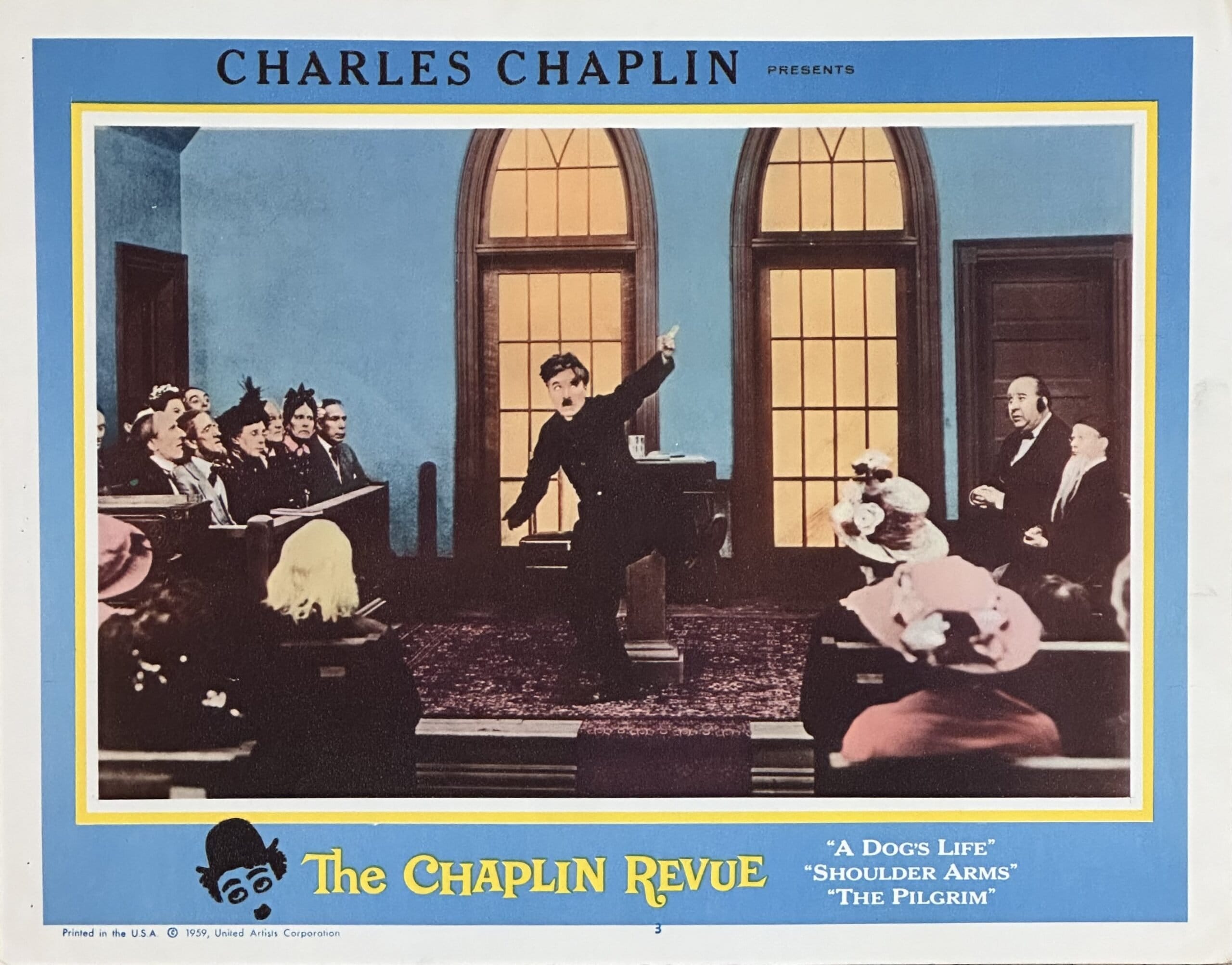

The Chaplin Revue

£150.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

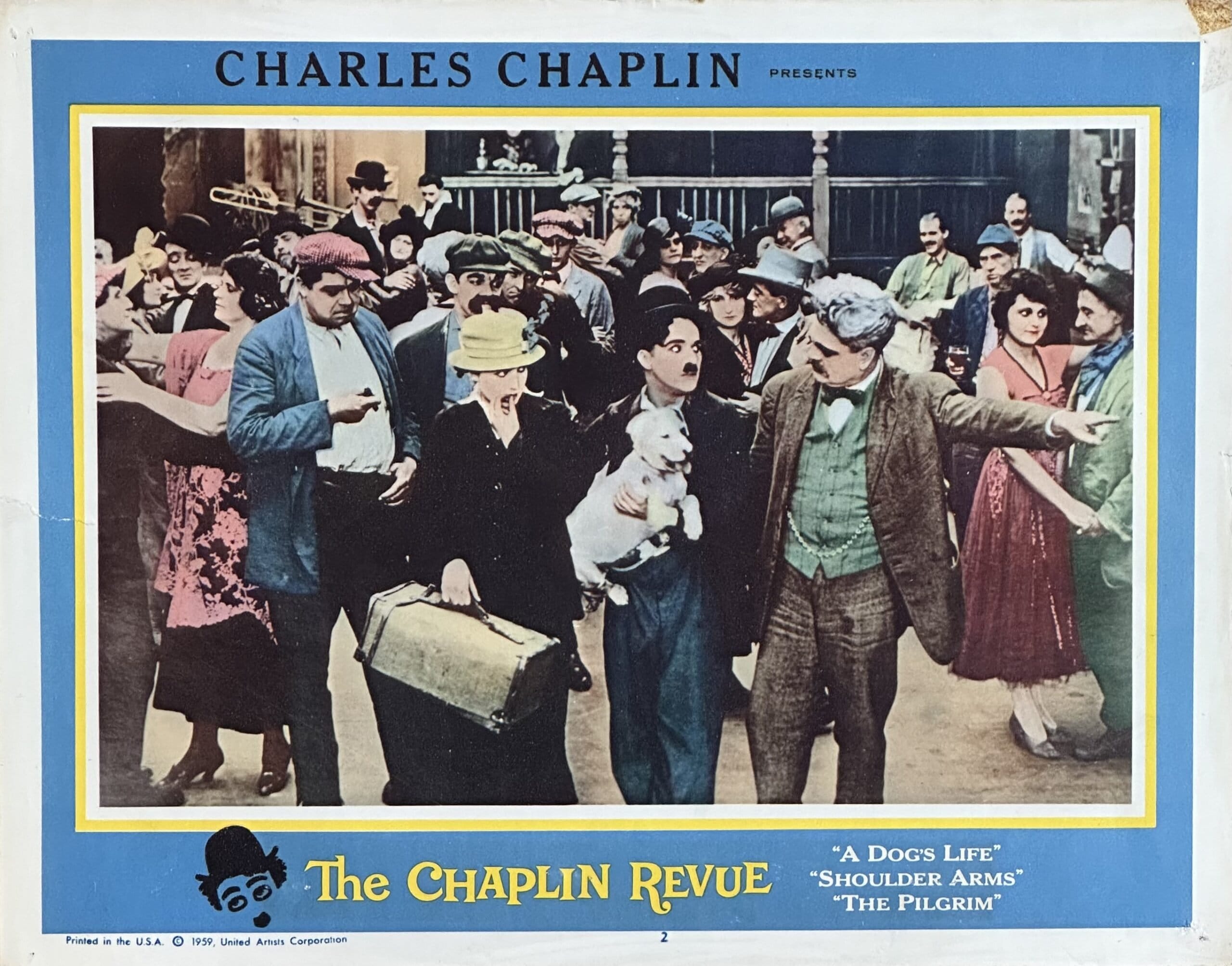

The Chaplin Revue

£150.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

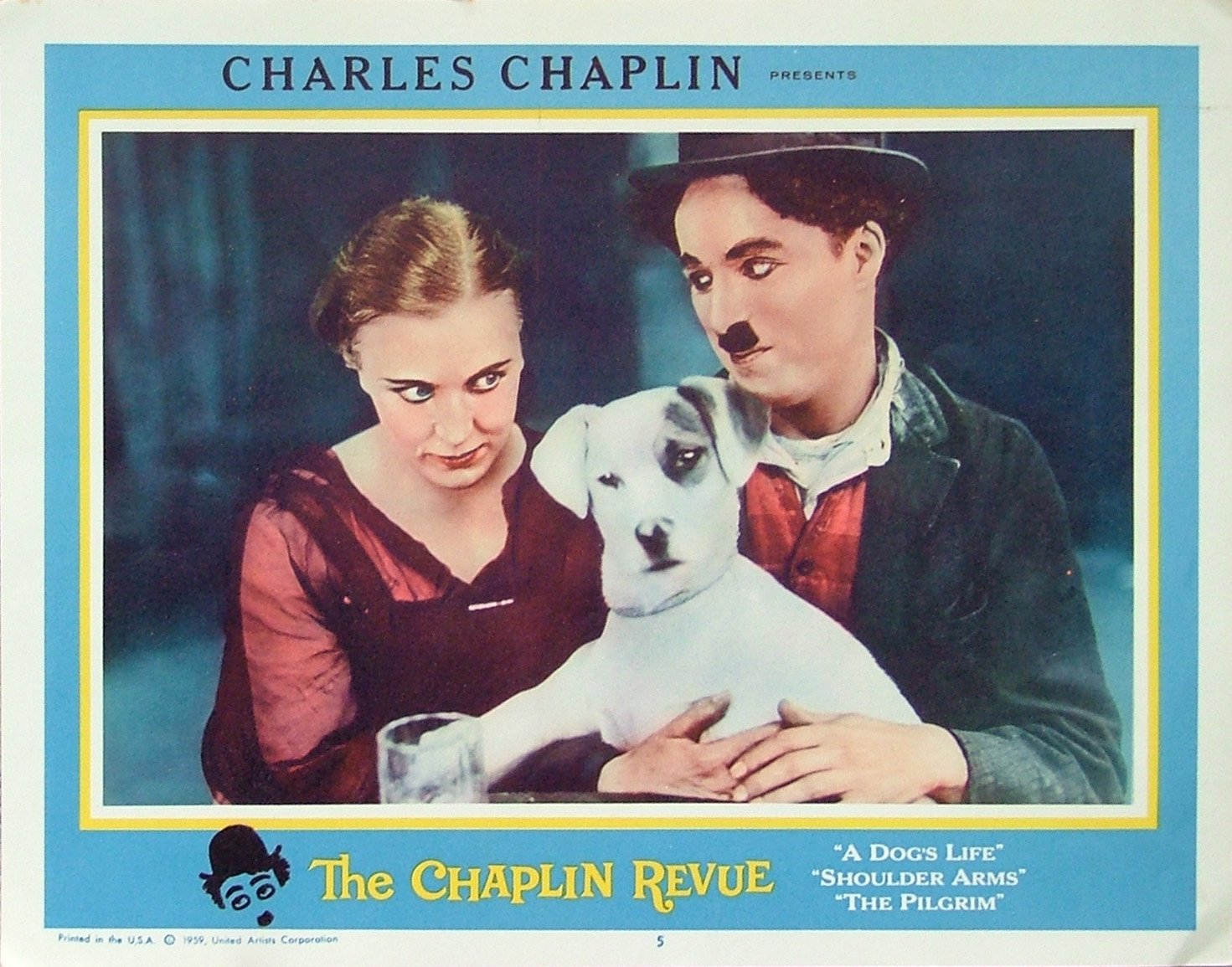

The Chaplin Revue

£175.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

The Gold Rush

£275.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

The Gold Rush

£350.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

Modern Times

£150.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

The Great Dictator

£250.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

Modern Times

£125.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

Modern Times

£125.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

City Lights

£245.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

City Lights

£245.00In stock

Format: Lobby CardView -

Monsieur Verdoux

£1,250.00In stock

Format: QuadView -

Limelight

£1,050.00In stock

Format: QuadView -

A King in New York

£650.00In stock

Format: QuadView