Buster Keaton

The Great Stone Face, so-nicknamed because he didn't laugh or smile on camera, started his comedy life as a baby on the vaudeville stage in his parents' act. By the mid 1920s, his popularity as a silent film comedian was approaching Chaplin's. A century on, the debate continues - was Buster funnier than Charlie? Or is it apples and pears?

Buster Keaton began his performing life as The Human Mop in his parents’ vaudeville act. Being thrown around the stage by his father gave him a crash course in how to fall, and stood him in good stead for his early film appearances, as an increasingly important supporting player in the short comedies of his friend, Roscoe (Fatty) Arbuckle.

Fascinated by comedy and the mechanics of the whole film making process, Keaton had by 1920 progressed to his own short subjects, starting with “One Week”. A big hit at the time, it could still bring the house down over 80 years later when played with live musical support to a full Royal Festival Hall.

Writing, directing and starring, Buster quickly graduated to his own feature length comedies, beginning with 1923’s “Our Hospitality”.

His technical mastery was superb, and the engineer in him was in part responsible for the fact that in many of his films he was pitted against mechanical forces; – boats, ships, trains, cars and even houses. In others, he was up against the forces of nature – wind, storm and cyclone. And in others still, it was the forces of the rest of the human race which conspired against him en masse – whether convicts, swarms of would be fiancées or hundreds and hundreds of policemen, as in the classic “Cops”, the ultimate chase movie.

Keaton’s masterpiece was a relative failure on its initial release. 1927’s “The General” (his response to Chaplin’s “The Gold Rush”) was a near perfect fusion of drama, engineering and comic invention. The Civil War comedy bears repeated viewings, and frequently tops critics’ lists of all-time favourites since its, and Keaton’s, re-discovery in the early 1960s.

Right up there with it is 1924’s “Sherlock Junior”, not just funny, but also a clever and cinematically knowing enterprise, as Keaton steps in and out of the world on screen sixty years before Woody Allen’s “The Purple Rose of Cairo”. And 1928’s “The Cameraman”, which was also much more successful commercially on first release. Made at MGM, it also signalled the start of Keaton’s long downwards slide.

Beset by alcoholism, the coming of sound and his surrender to the big studio factory system, by 1932 he was co-starring with Jimmy Durante. By 1935 he was out of feature films, and spent most of the next ten years making a living in low budget short sound comedies made for small studios who provided cheap filler for the bottom of the bill.

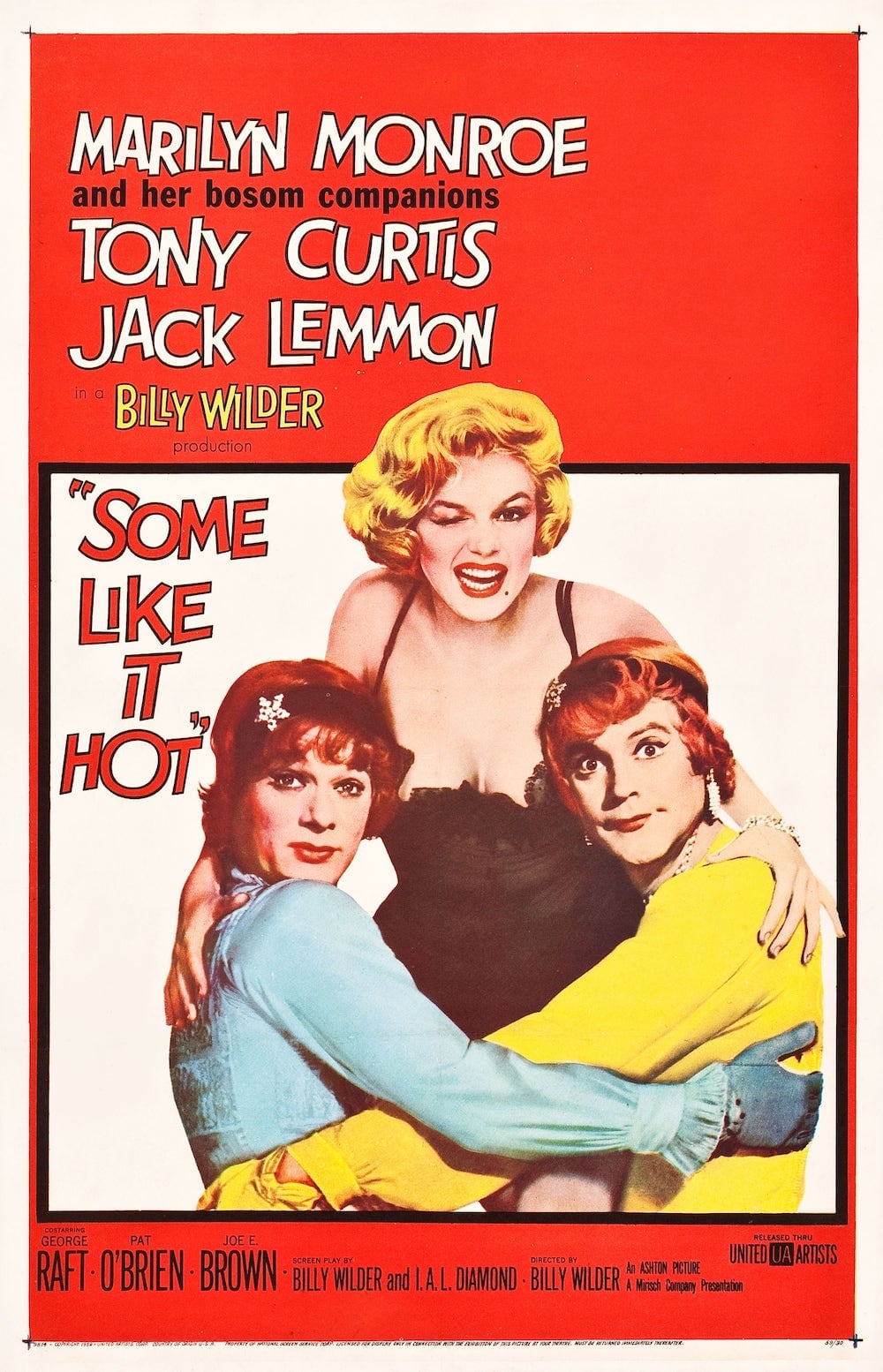

But he never stopped working, and like the character he played, simply refused to lie down. After James Agee’s influential “Life” essay in 1949 about the great silent comedians, Keaton’s gradually became a familiar face again. Cameos in big films (including Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard” and Chaplin’s “Limelight”), early television appearances, advertising commercials, a series of amusing supporting roles in early 1960’s beach movies, and even live appearances, showed that he was on the comeback trail.

He was still around and active when his early work was re-discovered by a new generation, so was able to combine film festival and revival appearances with new film work right up to his death in 1966. Poignantly, his last screen role was an important part in “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum”.

Some of our current Buster Keaton stock

-

Limelight

£1,050.00In stock

Format: QuadView